The Tao of Drawing-Cognitive Processes

Fundamentally, drawing is a valuable way of thinking and we use it to solve problems as well as to create art. I suggest that drawing is also a way of knowing, and the same could be said to be true of all our forms of expression. The reason for this is cognition. Cognition is “the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses (perception).”

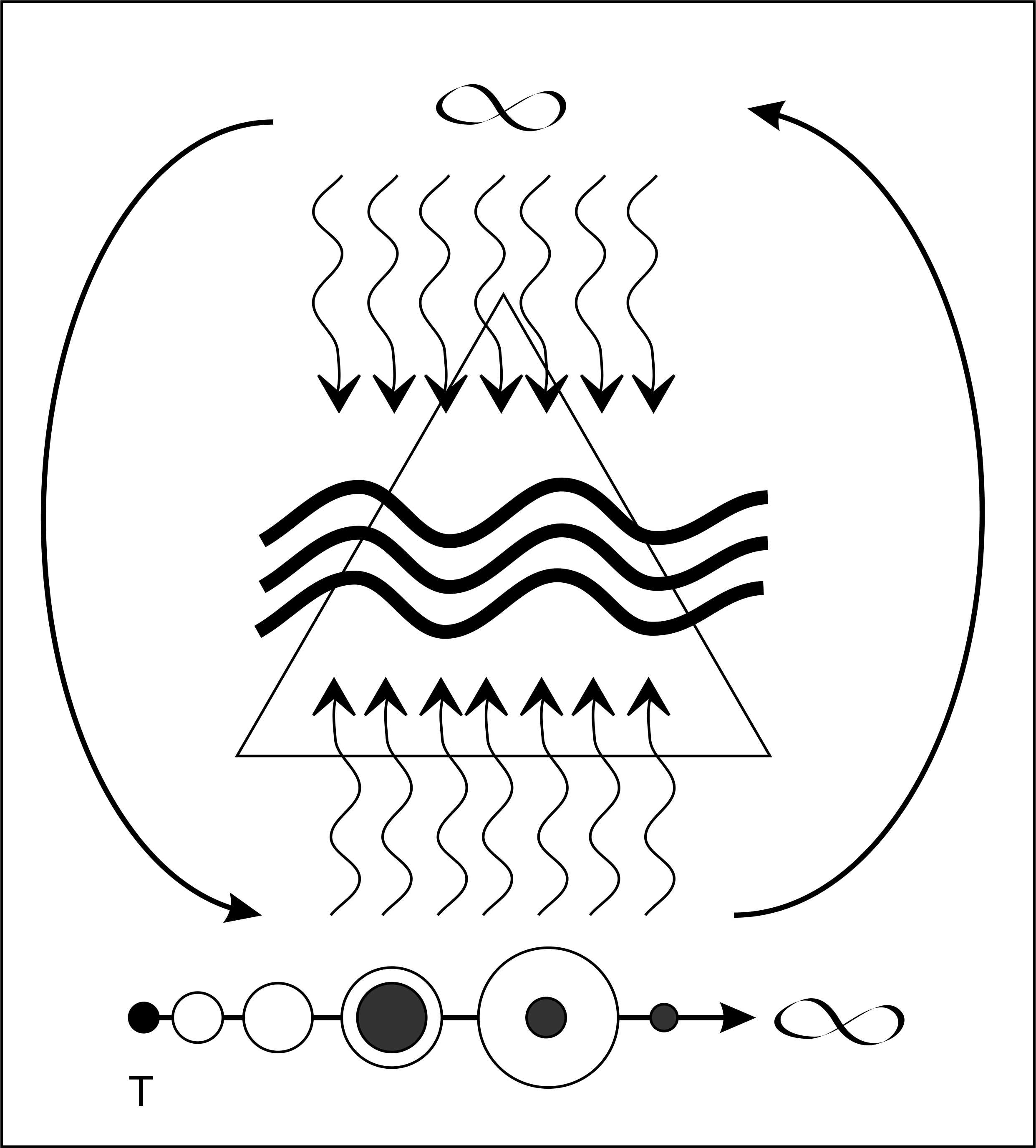

The diagram below is an effort to illustrate the process of cognition that begins with the mind from which flows as a stream of ideas and thoughts toward physical expressions, behaviors, and other thoughts. The stream passes through a sieve, or a filter. Our perceptions feed information to the mind and these are also filtered, but there are inputs and outputs that can bypass our filter altogether (The arched arrows on either side.) Our physical reality is bound by time, so it’s represented as a line that begins at “T” that progresses to infinity. The infinities here are based on possible choices, each with their own permutations (I’m not including a qualitative judgment about choices. The choices here are any kind.)

The cognitive process has a refining and expanding influence on knowledge represented here by circles placed on the timeline. Our knowledge base can increase (the circle increases) while at the same time our ability to distill and simplify a single subject can also increase (the circle decreases). Our focus can become quite intense.

Cognition is the driving force of individual human development with the potential for expansive affect.

An example.

Consider the cube. If you are very young, you probably wouldn’t care about a description of one. Instead, you’d play with one that is decorated with letters and numbers. Sometime later, you’d take several cubes and line them up and then as you developed some dexterity, you’d stack them and take pleasure in knocking them down again. For a long time they would just be toys and blocks. As more time passes, you might learn how a cube is defined, and how to measure one. Maybe you never think about your toys as cubes, much less draw one. Or two. Or many. You might not think about using a cube to locate a shape in space and define volume, or how to break a cube down into other shapes and volumes, or realize the relationships of spheres and cubes.

The science of child development points out the cognitive skills that we hope will develop as we grow. The ability to hold our attention (focus), recall of information, logic and the ability to reason, the ability to understand and interpret sensory stimuli, and over time the ability to quicken these skills to think faster and with greater clarity. Artists often lament the loss of a child’s artistic freedom. But I don’t think that learning to draw requires recapturing a childlike view of the world, even though scribbling can be joyful. Rather, we may need to consider the importance of our informed choices and the moment we decided our interests didn’t require us to refine our skills at something like drawing and set temporarily that aside.

In fact, art is in the minority of the uses for drawing. But, since I am an artist, drawing provides a lens for everything I see and think about; and the process of putting a mark on a surface, even in the sand with a stick, establishes a connection between my thoughts and physical reality that makes it possible to explore ideas with greater clarity, in part because thoughts have the potential to coexist with expressions as the thought and the expression reinforce the other. For example, if I think about “cube,” and then draw a cube, that process and attempted result create a memory of the notion of “cube” as well as reinforce and possibly change the original idea and the alteration of the first drawing so that the original ideation progresses, changes, refines, and becomes something more than a realistic representation of a cube. What that iterative process leads to, no one will know.

As I sit here and write this I’m organizing my thoughts at the same time that I write them. Writing is a linear process, but thinking is both logical and intuitive and non-linear. There’s no rule that says that can’t be so. But when I see and read what I write, I am inclined to edit it for the sake of good composition and better comprehension, not only for myself but for anyone who would dare to read it. Yet, for me, writing provides clarity of my own thoughts and evidence that a simple dialog between what’s in my head and what I write is taking place.

Let’s go back to the cube.

If you consider a cube, you likely know it has six sides. If you draw it as you imagine it from a position on a table, at most, you’ll only be able to see three sides. If you physically set a cube on the table yourself, you may remember the appearance of all sides and as you set yourself to drawing it, you can reasonably suppose that nothing about it has changed. That is the rule of perspective. The station point, your eye(s), provides a realistic point of view at the sacrifice of a literal understanding of what you cannot see, although you may know it, infer it, and interpret it.

Still, there are other ways of representing a cube.

You could, for example, photograph all sides and project those images onto a sphere. These days we can do that with the help of a computer. There was a time when the earth was flattened out and projected onto a cylinder. Gerardus Mercator did that in 1569. Pretty cool. Unwrap it and you have a rectangle.

Another way of representing a cube is by using orthographic projection. A very old, and very useful method of visualization. And while I think about it, the only limitations between a cube and any other volume or shape comes down to a matter of our tolerance for distortion and our intentions for the use of our conceptions and our native cognitive abilities to further manipulate that which we can visualize or recall from memory.

But, what is a memory?

There are different kinds of memory and all kinds share an electro-chemical structure through the interconnection of neurons. Although human memory is vast, it’s not always easy to access, nevertheless, we try to hold on to the beliefs, events, people, and skills that are important to us and revisit those memories and try to reinforce them. Although in the process they can become muddled (at least for me), nuanced, shaded, or slightly twisted depending on one’s state of mind. In the end, neurons hold data of different kinds related to our thoughts and perceptions. Likewise, the brain develops differentiation and structural relationships that more or less make it possible for us to have a sense of self and our place in the great wide world as we more or less find places to hold all the stuff we accumulate.

Humans have the ability to distinguish foreground and background and we can focus our attention on whatever we are inclined to do. Threats are pretty important. Sexual attraction. But also ideas. Notions of truth. Things out of the ordinary. Rules. Whatever.

Memories, then, are hierarchical. Many of the things in the background might be pretty fuzzy or altogether missing, while the foreground elements could be much stronger depending on the importance we ascribe to them. The reason that I mention this is that the word, “cube,” is generic. A construct of rules, so to speak. The block with painted letters and numbers is specific to an object you probably have known or seen and while it is cube-like, the number/letter block is probably reinforced by other important memories of people, smells, colors, events, and so on. Maybe you have a child who has blocks among their toys. You probably played with blocks when you were a child. Other memories may be connected with blocks, for example, the time in history when the paint used was tainted by lead. Memories can create threads that lead to other memories.

The cube, on the other hand, occupies the domain of “primitives.” Primitives are simple geometric forms and shapes. In a way, they are like blocks because we can build on them and make other things, or convey information for engineering, space planning, architecture, electronics, art. They are very versatile and useful. In computer modeling, primitives, like cubes, are used to become “other things.” But to do that we have to use procedures, processes, rules, algorithms, skills, imagination, visualization and so on that allow us to invent and create.

True, many people don’t draw and life goes along just fine and cognitive processes continue.

To be continued…

Cognition is the driving force of individual human development with the potential for expansive affect.

An example.

Consider the cube. If you are very young, you probably wouldn’t care about a description of one. Instead, you’d play with one that is decorated with letters and numbers. Sometime later, you’d take several cubes and line them up and then as you developed some dexterity, you’d stack them and take pleasure in knocking them down again. For a long time they would just be toys and blocks. As more time passes, you might learn how a cube is defined, and how to measure one. Maybe you never think about your toys as cubes, much less draw one. Or two. Or many. You might not think about using a cube to locate a shape in space and define volume, or how to break a cube down into other shapes and volumes, or realize the relationships of spheres and cubes.

The science of child development points out the cognitive skills that we hope will develop as we grow. The ability to hold our attention (focus), recall of information, logic and the ability to reason, the ability to understand and interpret sensory stimuli, and over time the ability to quicken these skills to think faster and with greater clarity. Artists often lament the loss of a child’s artistic freedom. But I don’t think that learning to draw requires recapturing a childlike view of the world, even though scribbling can be joyful. Rather, we may need to consider the importance of our informed choices and the moment we decided our interests didn’t require us to refine our skills at something like drawing and set temporarily that aside.

In fact, art is in the minority of the uses for drawing. But, since I am an artist, drawing provides a lens for everything I see and think about; and the process of putting a mark on a surface, even in the sand with a stick, establishes a connection between my thoughts and physical reality that makes it possible to explore ideas with greater clarity, in part because thoughts have the potential to coexist with expressions as the thought and the expression reinforce the other. For example, if I think about “cube,” and then draw a cube, that process and attempted result create a memory of the notion of “cube” as well as reinforce and possibly change the original idea and the alteration of the first drawing so that the original ideation progresses, changes, refines, and becomes something more than a realistic representation of a cube. What that iterative process leads to, no one will know.

As I sit here and write this I’m organizing my thoughts at the same time that I write them. Writing is a linear process, but thinking is both logical and intuitive and non-linear. There’s no rule that says that can’t be so. But when I see and read what I write, I am inclined to edit it for the sake of good composition and better comprehension, not only for myself but for anyone who would dare to read it. Yet, for me, writing provides clarity of my own thoughts and evidence that a simple dialog between what’s in my head and what I write is taking place.

Let’s go back to the cube.

If you consider a cube, you likely know it has six sides. If you draw it as you imagine it from a position on a table, at most, you’ll only be able to see three sides. If you physically set a cube on the table yourself, you may remember the appearance of all sides and as you set yourself to drawing it, you can reasonably suppose that nothing about it has changed. That is the rule of perspective. The station point, your eye(s), provides a realistic point of view at the sacrifice of a literal understanding of what you cannot see, although you may know it, infer it, and interpret it.

Still, there are other ways of representing a cube.

You could, for example, photograph all sides and project those images onto a sphere. These days we can do that with the help of a computer. There was a time when the earth was flattened out and projected onto a cylinder. Gerardus Mercator did that in 1569. Pretty cool. Unwrap it and you have a rectangle.

Another way of representing a cube is by using orthographic projection. A very old, and very useful method of visualization. And while I think about it, the only limitations between a cube and any other volume or shape comes down to a matter of our tolerance for distortion and our intentions for the use of our conceptions and our native cognitive abilities to further manipulate that which we can visualize or recall from memory.

But, what is a memory?

There are different kinds of memory and all kinds share an electro-chemical structure through the interconnection of neurons. Although human memory is vast, it’s not always easy to access, nevertheless, we try to hold on to the beliefs, events, people, and skills that are important to us and revisit those memories and try to reinforce them. Although in the process they can become muddled (at least for me), nuanced, shaded, or slightly twisted depending on one’s state of mind. In the end, neurons hold data of different kinds related to our thoughts and perceptions. Likewise, the brain develops differentiation and structural relationships that more or less make it possible for us to have a sense of self and our place in the great wide world as we more or less find places to hold all the stuff we accumulate.

Humans have the ability to distinguish foreground and background and we can focus our attention on whatever we are inclined to do. Threats are pretty important. Sexual attraction. But also ideas. Notions of truth. Things out of the ordinary. Rules. Whatever.

Memories, then, are hierarchical. Many of the things in the background might be pretty fuzzy or altogether missing, while the foreground elements could be much stronger depending on the importance we ascribe to them. The reason that I mention this is that the word, “cube,” is generic. A construct of rules, so to speak. The block with painted letters and numbers is specific to an object you probably have known or seen and while it is cube-like, the number/letter block is probably reinforced by other important memories of people, smells, colors, events, and so on. Maybe you have a child who has blocks among their toys. You probably played with blocks when you were a child. Other memories may be connected with blocks, for example, the time in history when the paint used was tainted by lead. Memories can create threads that lead to other memories.

The cube, on the other hand, occupies the domain of “primitives.” Primitives are simple geometric forms and shapes. In a way, they are like blocks because we can build on them and make other things, or convey information for engineering, space planning, architecture, electronics, art. They are very versatile and useful. In computer modeling, primitives, like cubes, are used to become “other things.” But to do that we have to use procedures, processes, rules, algorithms, skills, imagination, visualization and so on that allow us to invent and create.

True, many people don’t draw and life goes along just fine and cognitive processes continue.

To be continued…